BLOG

Lens changes your language.

Changing your lens is

like changing your language.

Like me, you are used to working with the same 35mm, a sudden shift to an 85mm can be intimidating.

It feels like starting from scratch and having to learn a new alphabet, new syntax.

It’s confusing, even destabilizing and the temptation to give up is great.

But photography is an art of perseverance. A photographer is fueled by doubts and uncertainty, and I love photography for that very reason.

You never know where you are going; or if it’s going to be any good.

It’s like digging a hole in the ground searching for gold and not knowing if there is any gold to be found.

This is how I was feeling the other

day when I put the lovely MF 85mm F1.4 on my Sony Alpha rii as

I was preparing for an all-day trek in La Réunion.

This tiny island in the Indian Ocean, located east of Madagascar, is a natural gem of valleys and volcanos, a paradise for trekkers. Each October, the island hosts ‘La Diagonale des Fous’, one of the most difficult Ultra Trails in the world. But we are getting away from our story here. As I was saying, I’m not a frequent 85mm user, since as a reporter, I prioritize angles from 24mm to 50mm. In my mind, the 85mm is a perfect lens for portrait photography as well as staged shows (concerts, opera, theatre, etc).

I never really considered this lens for landscape photography, and I am not the biggest fan of that field. So, I figured it would be a superb challenge to use the 85 mm on my trekking day, focusing on details instead of sprawling landscapes (which is what most people would be tempted to do in front of any jaw-breaking scenery - including myself).

There I was, sweating under the Indian Ocean sun and trying to keep up the pace with my friend.

Our objective was to walk down the slope of a volcano into a valley called ‘Grand Bassin’. From there, we would make our way to a waterfall and have lunch before heading back. The first thing I noticed about the 85mm was its weight, or lack thereof. It felt nice not to be bothered by the camera while I was descending the volcano. While the Samyang 85mm is not the most discrete lens, its weight seemed almost imperceptible!

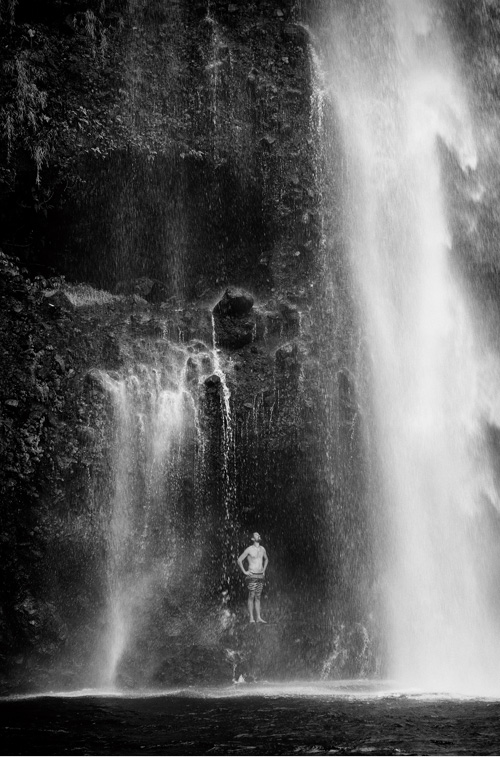

To add a little spice to my Samyang’s adventure, I chose to shoot in black and white, mostly because I think color landscape photography is boring and also because I am a big Ansel Adams fan. The walk down Grand Bassin went smoothly and when fine, we reached the waterfall, it was time for lunch, so we enjoyed the fresh water, relaxing our tired muscles and weary bones.

I then wanted to investigate the stabilization of the 85mm, so I took a coupled of shots from the waterfall with a slow speed shutter and was very pleased by the result once again.

It was soon time to end our little recreation and make our way back to our car. only this time going up. We had been foolish to think it would be fine to start the ascension after 4 pm. The heat hit us by surprise and it quickly dawned on us that the end of the trek would be a nightmare. Surprisingly, I managed to get some of my best shots while enduring a lot of unnecessary physical pain!

What I can say about the 85mm is that it is not the most practical lens if you are going to shoot subjects in

Being a manual lens, the focus is not always easy to get through the Sony viewfinder. I would recommend it for portrait landscape photography. and if you enjoy working calmly and taking your time, then it’s a good pick. If you are into sports photography, forget it. Over all, I wouldn’t say that the 85mm is my personal cup of tea, but that has nothing to do with Samyang. In fact, the lens surprised me during and after the shoot as I was looking at the pictures on my laptop (as featured) and found myself taken aback by how sharp the images were. While I will never be Ansel Adams and cannot speak for the man, I’m pretty assured he would have liked to give this lens a try!

Jeremy Suyker (b.1985) is a French documentary photographer and reporter specialized in sociocultural and contemporary issues. He engaged his career in 2011 to report on the aftermath of the Sri Lankan civil war. The following year he embarked for Myanmar where historical political changes were occurring. Jeremy travels to Iran since 2013, documenting the country’s rich culture and history. The Persian Factory, his piece on Tehran’s underground art scene, has been published worldwide. Parallel to his journalistic engagements, he is pursuing personal projects around the Black Sea region, Central Asia and Istanbul. His works can be found in The National Geographic, The Sunday Times Magazine, GEO, Newsweek Japan, The Washington Post, Stern, Der Spiegel, Internazionale, Le Figaro Magazine, L’Equipe Magazine, Slate and 6Mois.

MF 85mm F1.4

MF 85mm F1.4

SONY

SONY

F1.0

F1.0

1/320 sec

1/320 sec

1000

1000

Multi-Segment

Multi-Segment

-

-

-

-

-

-

MF 85mm F1.4

MF 85mm F1.4

SONY

SONY

F1.0

F1.0

1/100 sec

1/100 sec

1000

1000

Multi-Segment

Multi-Segment

-

-

-

-

-

-